Why I Don't Ask My Daughters What They Want to Be When They Grow Up

Career ladders are gone and safe jobs are dangerous. Here's why building a portfolio matters more.

Henning Voss

11/26/20257 min read

When Career Plans Became Obsolete

Last week at breakfast, one of my nine-year-old daughters told me she wants to be a singer when she grows up. Her twin sister, without missing a beat, said she wants to join and form a band.

There’s a standard script adults tend to follow in these moments. We smile, maybe ask a few encouraging questions, and then file it away in the “cute things kids say” folder.

My daughters are only nine, and their plans will probably change by next week. But lately, whenever they talk about their futures, I can't shake a feeling: the question itself, "What do you want to be when you grow up?" feels outdated. It's a relic from a world where careers were ladders you climbed, not waves you surfed.

I also meet recent graduates (bright, hardworking, often heavily indebted) who still act as if the old system is intact: get a degree, land an office job, move up. Except that system is quietly collapsing underneath them.

In conversations, in the data, and in the stories emerging from tech, consulting, and finance, the same pattern keeps showing up: career planning, as we were taught to think about it, simply doesn’t map to the world that’s emerging.

So if the old roadmap is gone, what replaces it?

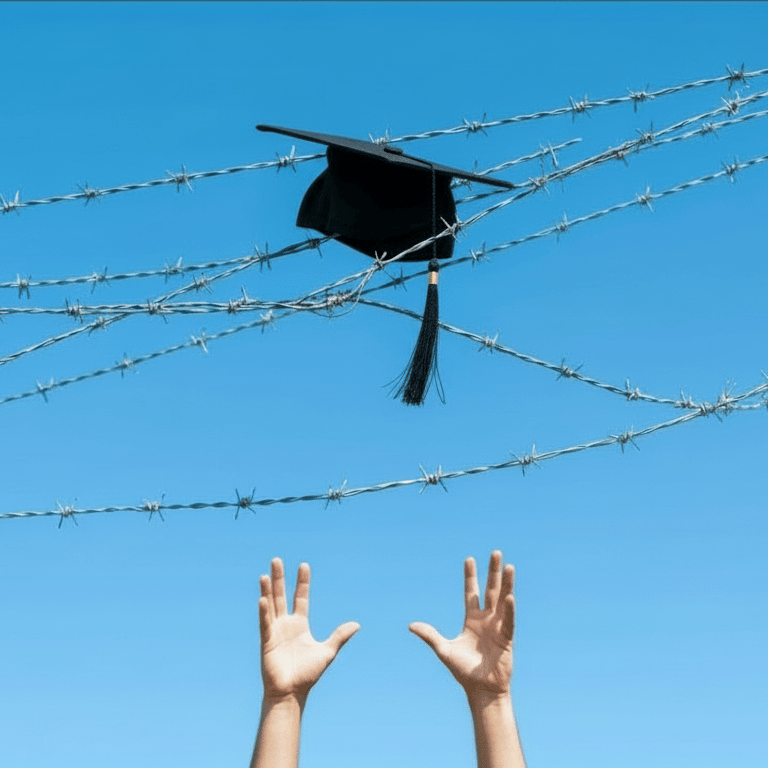

The Degree is No Longer a Safety Net

The old promise was simple: go to college, get a degree, get a job. But that transaction has broken down.

In the US, tuition has risen nearly 900% since 1983, saddling borrowers with $1.8 trillion in debt.

Peter Thiel famously compared the university system to the Catholic Church before the Reformation: a priestly class dispensing expensive salvation (the diploma) while implying that without it, you're damned.

But the labor market is no longer buying that salvation. As companies like Amazon and UPS cut white-collar roles in favor of leaner teams and AI, the "safe" office job is becoming an endangered species. Meanwhile, demand for skilled trades is booming. Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, said it bluntly: "If you're an electrician, a plumber, a carpenter, we're going to need hundreds of thousands of them."

This makes me think of a childhood friend in Germany who became a carpenter. While we chased corporate titles, he built a bespoke business. Today, he has the autonomy, craftsmanship, and job security many office workers have lost.

To make matters more complex, the half-life of formal knowledge has shortened. An MIT administrator once quipped that the university could build a nuclear reactor faster than it can change its curriculum. By the time a student graduates, much of what they learned freshman year is already obsolete.

Employers are losing faith that a degree equals competence. They're dropping degree requirements in favor of what Peter Diamandis calls the "self-credentialed" economy. They don't care what your transcript says, they care what you can prove you can do.

The gates are open, but the safety net is gone.

From Career Ladders to Skill Portfolios

So if the old question (What do you want to be when you grow up?) no longer makes sense, what replaces it?

The most practical framework I've found comes from venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, who argues we need to abandon the 'passion' mindset entirely. He advises young people to build concrete, real-world skills early, ideally through degrees with technical or quantitative depth (engineering, computer science, hard sciences, mathematics, economics) because they teach you to do hard, useful things and train your mind to think with logic and data.

If your undergraduate degree isn't technical, he suggests layering on a practical graduate degree. Useful combinations, in his view, include engineering + MBA, computer science + physics, or physics + economics. The idea is not prestige for its own sake but optionality, skills that compound.

From there, Andreessen essentially tells you to stop obsessing over "the perfect plan" and instead build what he calls a multi-threat profile. He borrows Scott Adams' "top 25% strategy": there are two ways to build an extraordinary career. One is to become the best in the world at a single thing (incredibly rare). The other is to become very good (top 25%) at several things and combine them, so your specific mix is rare.

Take Scott Adams. He isn't the world's best cartoon artist. He isn't the funniest writer. But he is in the top 25% of both, combined with a background in business. That specific intersection created Dilbert. You don't need to be the best. You just need to be the only one in your intersection. Andreessen notes that most CEOs are like this: not world-class in any single discipline, but top quartile in several (strategy, communication, sales, finance, leadership). To make that concrete, he recommends layering five “leverage skills” on top of whatever technical or domain foundation you build:

Communication: written and verbal

Management: understanding how people and organizations work

Sales: persuasion and negotiation

Finance: how money actually flows

International exposure: operating in different markets and cultures

The combination, a substantive base plus a stack of leverage skills, is what makes you “rare and valuable” over time.

There’s a deeper layer to his advice that I find especially relevant for the AI era. Andreessen argues that every job has two layers:

A tactical layer: doing excellent work, building skills, earning a reputation.

A strategic layer: using the job as a learning laboratory to understand how industries and businesses actually function.

In practice, that means asking questions like: If I were starting this company from scratch today, what would I do? How is this industry likely to change over the next decade? Which customers are underserved? Which technologies could upend this model?

If you treat each role that way, he says, you don’t need a rigid career plan. You’re steering yourself, repeatedly, into high-opportunity environments (ideally industries where founders are still around and the game is still being invented), and extracting skills and insight as you go. When you combine this with the broader shift in how we credential and learn, you end up with something like a new playbook:

Don't plan your career. Build a portfolio of skills, experiences, and projects that AI can't easily copy, and keep updating it.

In that sense, my carpenter friend is playing the same game. He has a rare combination of craft skill, taste, client management, and small-business savvy. You can’t download that as an app. You have to build it, piece by piece, over years.

What We Should Actually Teach (Our Kids and Ourselves)

This all sounds grand in the abstract. But breakfast comes every morning. My daughters will keep asking. So what do we actually teach them, and the recent graduates who still believe in a ladder that isn’t there? Here’s the playbook I wish someone had handed me at 18, broken down into three shifts.

Phase 1: The Mindset Shift

Stop asking "What do you want to be?" Asking this freezes a nine-year-old in a false certainty. The better question is: "What are you curious about right now, and what can you build around that?" The goal is to make trying things out normal, not locking in too early.

Get used to real risk, early. Marc Andreessen warns against the "orchestrated childhood": kids who are polished but untested. It’s better to let small failures happen early when the stakes are low. Treat these moments as training for a world where certainty is permanently in short supply.

Seek out "founder energy." Whenever possible, position yourself near the people shaping the game. Don't just look for a job description; look for a learning laboratory. Keep one eye on the tactical (doing the work) and one eye on the strategic (learning how the business works).

Phase 2: The Skill StackBuild a "Top 25%" Skill Stack. Don’t obsess over being the best in the world at one thing. Instead, follow the Scott Adams approach: become "top 25%" at three things that combine well. For example: Data Analysis + Storytelling + Healthcare. That specific intersection is rare, valuable, and hard to automate.

Learn to grow revenue. Whether you’re in engineering, design, or product, the ability to move the top line (to bring in customers or sales) is the single most portable skill you can possess. Demonstrable proof ("I helped add $1M in sales") beats almost any university credential.

Build a visible portfolio. In a world of self-credentialing, your output is your resume. GitHub repos, design portfolios, newsletters, side projects, anything that proves you can create value in the real world is now your primary asset.

Phase 3: The New ToolsTreat university as a tool, not a religion. If you go, choose fields that build durable, transferable skills (math, hard sciences, economics). Andreessen suggests aiming for 18 months of real-world work experience before you even graduate. Grades matter, but the portfolio of what you’ve actually done matters more.

Use AI as a tutor, not a crutch. AI is the best educator in history: infinite patience and near-zero cost. The advantage belongs to those who use it as a lab partner to learn 10x faster, rather than just using it to bypass the effort of thinking.

Back to the Breakfast Table

I still don’t have a neat answer for my daughters when they tell me they want to be a dancer, a singer, a vet. And perhaps that’s the point.

What I can honestly say is something like this: You don’t have to know what you’ll “be.” But you do need to get very good at learning, at noticing what matters, at building things other people find valuable, and at staying human in a world full of smart machines.

If I could send one message into the future they’ll inhabit, it’s this: you’re not choosing a career, you’re building a portfolio of skills, of experiences, of relationships, of experiments. That portfolio will evolve. Pieces will become obsolete; new ones will emerge. AI will both disrupt what you do and teach you how to do the next thing.

Career planning may be dead. But careers themselves (as evolving, messy, creative projects) are very much alive.

The real work, for all of us, is to keep learning fast enough, bravely enough, and honestly enough that we don’t outsource our agency along the way.

Over to You

If you were sitting across from a 17-year-old today (or your own nine-year-old at breakfast) what would you tell them about work, learning, and the future?

And just as importantly: how different is that from the advice you once received yourself?